By Isaiah Colbert

Databases are useful tools, but some are so flawed they should be abolished, said panelists appearing at the Chicago Headline Club’s FOIAFest 21 on Sunday.

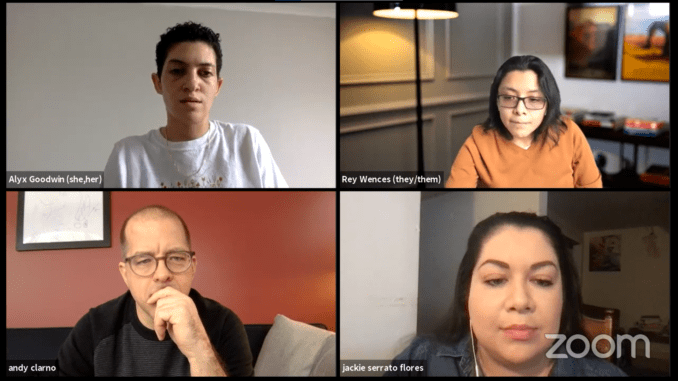

Andy Clarno, an associate professor and coordinator of the Policing in Chicago Research Group at University of Illinois at Chicago, highlighted the many problems he sees with the Chicago Police Department’s gang database.

For one, a person’s name can be added to the database without any evidence being provided.

“If police stop a young person of color in a neighborhood that the police considered to be getting territory or with people that they considered to be gang members, then they had that person to the list, too,” he said.

People do not have to be arrested to be added to the gang database, Clarno said.

Chicago’s gang database has led to an increase in deportations by ICE and immigrants have had their DACA applications or renewals turned down because they’re names are listed in the database.

Jackie Serrato, editor-in-chief of the South Side Weekly, said the gang member label cannot be expunged or removed from people’s records.

“Some of the demands of the Invasive Database Campaign is for there to be due process for not just adding someone to the system, but for removing their names once they serve their time, realize they were added erroneously or have moved on to live law-abiding lives,” Serrato said.

Rey Wences, strategic communications organizer for Erase the Database, said there is a sense of harassment experienced by people who have their information entered into databases like Chicago’s gang database.

“The city likes to say that we are a sanctuary city and that there was no police-ICE collaboration,” Wences said. “However, one of the loopholes that was around was there could be police-ICE collaboration if an individual was in the gang database.”

Erase the Database wants to ensure undocumented immigrants can submit a Freedom of Information Act request without fear of retaliation from ICE or the CPD.

Although the office of the inspector general suggested ways to fix the database, Alyx Goodwin, organizer at Black Youth Project 100, said their goal is to abolish it.

“It’s still important for us to push back even when these sorts of findings come to light,” Goodwin said.

The panelists said journalists can do their part by continuing to submit FOIA requests, not be fearful of litigating a rejected FOIA and link their findings within articles so organizers can access them.

Goodwin said journalists need to push back on the idea that journalism is objective and stories about the gang database need to take some sort of middle ground.

“Our organizing needs that kind of support from journalist and media to stand firmly in understanding these are wrongs and harms caused to our communities,” she said.